A deep, ideological component in the furious debate over “repealing and replacing” the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”)–as it was in the furious 2009-10 debates over the ACA’s passage, the 1993-94 failed Clinton health care plan, Johnson’s 1965 Medicare and Medicaid initiatives, and still earlier–is the opposition of two world views about health care.

On one side, health care is a right, just like equal protection of the law, free speech, and childhood education; it therefore must be in some fashion provided by government. (This is, for example, Bernie Sanders’ position.) On the other side, health care is a commodity individuals can choose to buy, just like clothes, housing, or iPhones, and therefore not a responsibility of government. (For two recent defenses of this position, see Shapiro and, more nuanced, Ponnuru.) The realpolitic of the current debate, of course, involves taxes, spending, vested interests, political promises, and a lot more than philosophy. But philosophical division is entwined in the long history of health care controversies.

Physician working with the Farm Security Administration, Missouri, 1939. (Source.)

Most Americans, like most citizens of western countries, say that “providing health care for the sick” should be “the government’s responsibility,” but Americans are less unified and insistent on that than are other westerners.[1] And we have the weakest public system of health care for the non-elderly in the West. That may be why Americans are much more likely than citizens of other affluent nations to report having in the previous year gone without medical treatment that they needed.[2]

Americans have generally leaned toward the “human right” position on health care–if not in those exact words–but in recent years party polarization has increasingly colored the recurrent debates. So has generational politics.

Health Care and Politics

Many survey questions have probed Americans’ views about health care policy–although I haven’t yet found a survey that asks explicitly about health care as a “right.” (See this 2016 review for a canvas of recent polls.) Nonetheless, the General Social Survey has used two similar items for almost 40 years that get at the idea and that allow some historical perspective on Americans’ views about who is responsible for health care.

One GSS question, asked five times over about three decades, reads, “On the whole, do you think it should or should not be the government’s responsibility to . . . provide health care for the sick?” In 1985, 36% of respondents picked “definitely should,” 48% picked “probably should,” and 16% picked probably or definitely should not. In 2016, 49% said definitely, 37% probably, and 13% said it is not a government responsibility. Thus, strong support for government responsibility strengthened a bit over the two decades, from 36 to 49 percent, albeit rising and falling over those years.

Another question, using slightly different wording, was asked much more often. Interviewees’ responses do not display as strong a consensus but still a similar trend. The question reads:

In general, some people think that it is the responsibility of the government in Washington to see to it that people have help in paying for doctors and hospital bills; they are at point 1 [on this 5-point scale]. Others think that these matters are not the responsibility of the federal government and that people should take care of these things themselves; they are at point 5. Where would you place yourself on this scale, or haven’t you made up your mind on this? [3]

In 1983-84, 46% said that Washington should be responsible, 21% picked the self-responsibility side, and 33% said that they agreed with both sides. In 2014-16, the distribution was identical. Nonetheless, there had been some changes in between. Whenever a major health policy initiative was under debate, support slumped. More importantly, Americans’ positions on the issue became polarized by political party, as shown in this figure.

In 1983-84, Democrats and Republicans differed by 22 points in endorsing government responsibility; in 1991, they differed by only 14 points; but in 2014-16, they differed by 41 points. The sharpest drops in Republican support occurred when the Clinton plan was on the table, between 1991 and 1994, and when Obamacare was passed, between 2008 and 2010. (A series of Gallup polls in the 2000s using a similar question showed about 60% support until 2009 and then a drop to about 50% afterwards.) Whatever else is happening in the current health care debate, it has gotten much more entangled with political competition than earlier debates.

Generations

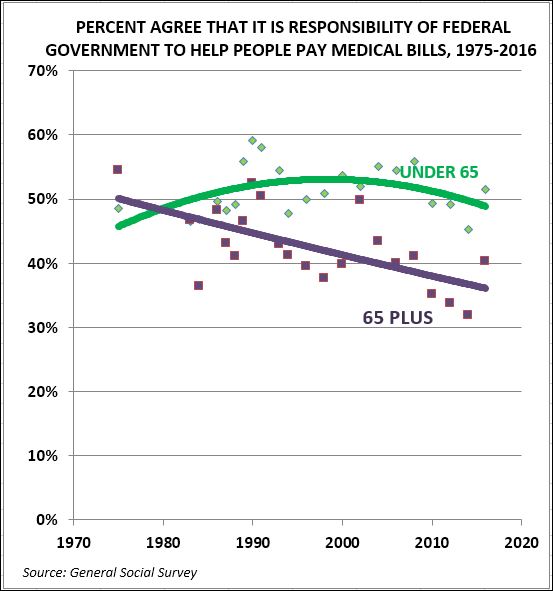

The party cleavage on health care as a right is not the only division. The next figure shows the same data separating the answers of respondents aged 65 and older from those aged 18 to 64.

In the early years, the two groups saw the topic alike, but by the 2010s, senior citizens were less likely to invoke federal responsibility than were Americans under 65. (A similar trend appears for the other form of the question.) The irony, of course, is that these seniors are all the beneficiaries of a huge federal health care program, Medicare. Doubling the irony is that many of the elderly respondents who are reluctant to endorse federal responsibility these days–roughly one in five of them–endorsed it 30 years earlier.[4] Many of my fellow Medicare-card carriers seem to have an “I’ve got mine, Jack” attitude.

Still, the bottom line is that Americans are much likelier to express views suggesting that health care is a right than views suggesting that people should be on their own, although they are not as united nor as effective on the issue as citizens in the rest of the first world. Except for the senior citizens–who have claimed a medical care right since the 1960s–that government responsibility has yet to be fully shouldered.

————————————

NOTES

[1] In the International Social Survey Programme study of 1990 over 10 percent of U.S. respondents did not agree with that idea; this was the highest percentage of “no” answers among respondents from 11 affluent nations. Forty percent of Americans in the poll said that health care was definitely (rather than just probably) a government responsibility–which, together with the Australians, made them the least definite supporters among all the national samples.

[2] In the World Values Survey of 2010-12, over 20 percent of U.S. respondents said that they or their family had gone without needed “medicine or medical treatment” in the previous 12 months. Next highest among ten other advanced nations were the New Zealanders, at 12 percent. (The percentage who said they went without was under four for the Germans, Dutch, Spanish, and Japanese.)

[3] The insertion of “Washington” and “federal” in this question surely pushed some respondents away from the “yes” position.

[4] This claim is based on “synthetic” cohorts. I compare the answers of 65-to-74 year-olds and of 75-to-84 year-olds in 2010-12-14 to those of 35-to-44 year-olds and of 45-to-54 year-olds respectively in 1983-84-86. These were not the same individuals, of course, but were the same birth cohort at both times. The difference in the proportion of “definitely should” plus “probably should” answers between the matched cohorts suggest a one-in-five conversion from support to ambivalence or opposition as they aged, as they gained Medicare.