One of the leading economic historians of the American south, Stanford’s Gavin Wright, observes in a recent Journal of Economic Perspectives article that both 19th-century defenders of slavery and 21st-century critics of slavery credit it for the rise of modern industrial capitalism. Southern “King Cotton” was, goes the argument, the cheap ingredient that grew the critically important northern textile factories that propelled industrialization.

The 19th-century group claiming slavery’s necessity was trying to preserve the South’s “peculiar institution.” The 21st-century group, composed of “New Historians of Capitalism” and many writers on the Black experience (such as contributors to the New York Times “1619 Project”), is trying to show that American affluence today was built on the backs of slaves and, by extension, to show how much Americans today owe the descendants of those slaves.

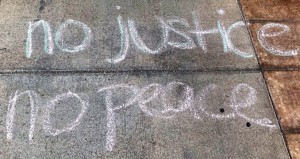

Library of Congress http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a37040

Wright, while never underestimating the moral abomination of slavery and, later, serfdom, their long-lasting harms, and the complicity of Americans beyond the slave-owners themselves, objects: The proposition that slavery powered industrialization “has been rejected by virtually every economic historian who has examined the issue.” In the end, “slavery enriched slave-owners, but impoverished the southern region and did little to boost the US economy as a whole.” (Another historian of the South has a harsher rejection here.) Wright tip-toes around the connected reparations issue. But on this Juneteenth, the connection warrants more attention.